𝐁𝐚𝐭𝐭𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐇𝐲𝐝𝐫𝐨𝐢𝐝𝐬: 𝐓𝐢𝐩𝐬 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐈𝐝𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐟𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐂𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐫𝐨𝐥

Introduction

Hydroids—a word that strikes frustration into many a saltwater aquarist. These tiny, stinging organisms can sneak into your tank unnoticed, but once they take hold, they’re often a challenge to remove. Whether they’re clinging to your rockwork, waving on frag plugs, or hitchhiking into your display tank, hydroids have the potential to disrupt your carefully balanced reef system. But are they always villains? Let’s dive into what hydroids are, how to manage them, and how to stop an outbreak before it begins.

What Are Saltwater Hydroids?

Hydroids are small, stinging invertebrates belonging to the phylum Cnidaria, making them close relatives of jellyfish, corals, and anemones. They have a fascinating and complex life cycle that includes both polyp and medusa stages, with different hydroid species thriving in diverse marine environments.

Key Characteristics of Hydroids:

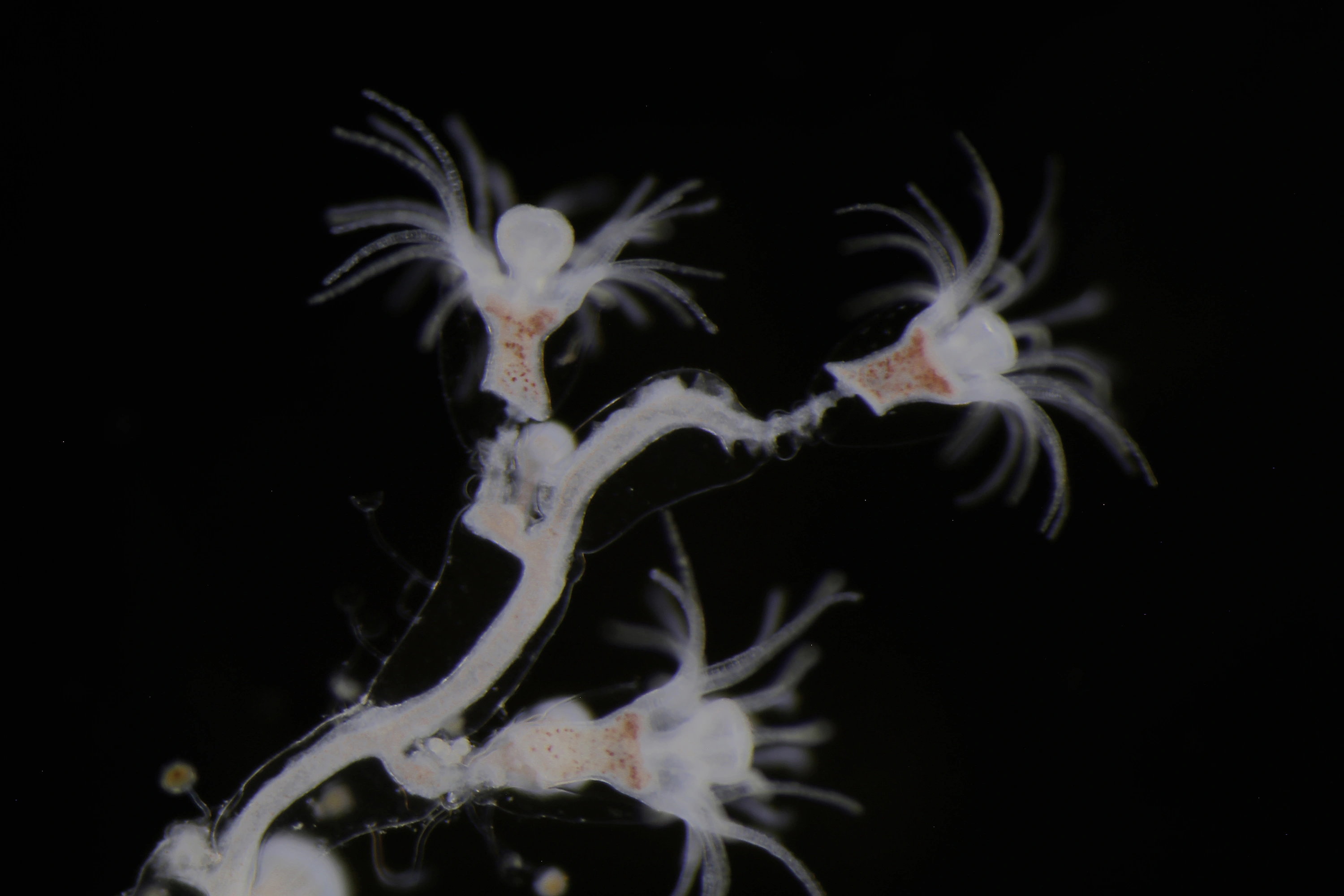

- Size and Appearance: Ranging from microscopic to visible colonies, hydroids often have branching, feather-like, or filamentous structures.

- Stinging Cells: Like their jellyfish cousins, hydroids use nematocysts to capture prey and deter threats.

- Growth Habits: Hydroids attach to hard surfaces like rocks, coral skeletons, and tank glass. Some species are solitary, while others form dense colonies.

Common Types of Hydroids in Aquariums:

Hydroids are fascinating yet often problematic organisms in reef aquariums. They come in various forms, ranging from mat-like colonies to solitary polyps, and their ability to spread rapidly or harm other tank inhabitants makes them a challenge for hobbyists. Below is breakdown of the common types of hydroids you may encounter in aquariums:

- Colonial Hydroids: Grow in mat-like structures and spread quickly.

- Solitary Hydroids: Individual polyps that are less aggressive but still invasive.

- Medusa-Producing Hydroids: Develop into free-swimming medusa, which complicates eradication efforts.

- Bright Orange or Red Hydroids: Tubular stalks, known for their striking appearance and rapid spread in nutrient-rich environments.

- Sea Ferns: Another type of colonial hydroids resembling intricate underwater ferns that spread aggressively and compete with corals for space.

A Deeper Dive into Each Type

Colonial Hydroids

Description: Colonial hydroids form dense, interconnected mat-like structures (They resemble vines to me) that can rapidly cover rockwork, frag plugs, or other tank surfaces. These colonies are made up of numerous polyps, each specialized for feeding, reproduction, or defense.

Growth Characteristics:

- Rapid spread due to their ability to fragment and regrow.

- Often have a feathery or web-like appearance, making them visually distinct.

- Thrive in nutrient-rich environments.

Challenges:

- Their rapid growth can smother corals and outcompete other beneficial organisms for space and resources.

- Removing colonial hydroids manually is difficult because even small remnants can regrow.

Example Species: Eudendrium spp. (often seen as hitchhikers on live rock).

Solitary Hydroids

Description: Solitary hydroids are single, independent polyps rather than interconnected colonies. They often resemble tiny anemones with tentacles extending outward.

Growth Characteristics:

- Less aggressive than colonial hydroids but can still reproduce through budding.

- Found attached to rockwork, sand, or even snail shells.

Challenges:

- Though slower to spread, solitary hydroids can still sting and harm nearby corals.

- They are often overlooked because they are smaller and more isolated, allowing them to persist unnoticed.

Example Species: Hydractinia spp. (frequently found on hermit crab shells).

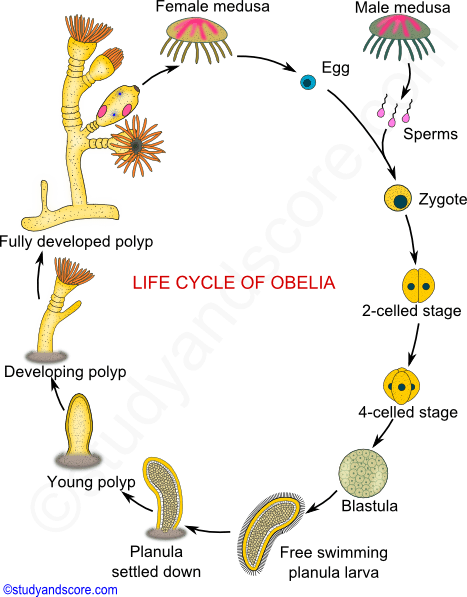

Medusa-Producing Hydroids

Description: Some hydroids have a more complex life cycle, producing free-swimming medusa during their reproductive phase. These medusa resemble tiny jellyfish and can disperse widely in the tank.

Growth Characteristics:

- The medusa stage can release fertilized eggs into the water column, resulting in new hydroid colonies forming throughout the tank.

- The swimming medusa are small and nearly transparent, making them difficult to spot and control.

Challenges:

- The ability to spread via medusa makes eradication significantly more difficult.

- Even if the main colony is removed, medusa swimming in the water can establish new colonies in other areas.

Example Species: Obelia spp. (a common species that alternates between polyp and medusa stages).

4. Orange or Red Hydroids

Description: Visually striking with bright orange or red stalks topped by polyp-like structures. They grow as individual polyps or in loose colonies, adding a vivid splash of color to rockwork or tank glass.

Growth Characteristics:

- Grow as solitary or sparse colonies, often attaching to hard surfaces like live rock or shells.

- Spread quickly in tanks with high nutrient levels and low water flow.

- Can proliferate in shaded areas, making detection more difficult.

Challenges:

- Their attractive appearance often delays removal, but their stinging cells pose a threat to corals and other organisms.

- They are difficult to remove completely, as their tubular stalks can fragment and regenerate.

- Can quickly dominate small areas of the tank if left unchecked.

Example Species: Tubularia indivisa (commonly seen on wild-collected live rock).

5. Sea Ferns

Description: "Sea ferns" are colonial hydroids with intricate, branching colonies that resemble underwater plants or ferns. They are invasive and known for rapid spread.

Growth Characteristics:

- Form dense, mat-like colonies that cover rockwork, substrates, or even coral bases.

- Reproduce both sexually (via medusa stages) and asexually (through fragmentation), enabling rapid growth and spread.

- Thrive in areas with low to moderate flow and elevated nutrients.

Challenges:

- Their aggressive growth can smother corals and compete for space and resources in the tank.

- Colonies are difficult to remove manually, as fragments left behind often regenerate.

- Their medusa stage complicates eradication, as it allows for dispersal throughout the tank.

Example Species: Aglaophenia pluma (often hitchhikes into tanks on live rock or frag plugs).

Identifying Hydroids in Your Tank

Proper identification is crucial for managing hydroids effectively.

- Visual Clues:

- Colonial hydroids resemble tiny, feathery plants.

- Solitary hydroids often look like miniature anemones.

- Where They Grow: Common on live rock, substrate, frag plugs, or even corals.

- Behavior: Hydroids retract when disturbed and thrive in areas with low flow.

- Common Mistakes: Hydroids are often confused with algae, sponges, or harmless filter feeders.

Are Hydroids Always Harmful?

Not all hydroids are tank-wrecking villains. In small numbers, they can even benefit your aquarium by contributing to biodiversity or serving as a food source for specific tank inhabitants. However, left unchecked, hydroids can cause serious problems:

Benefits of Hydroids:

- Provide a natural food source for herbivorous fish and invertebrates.

- Add biodiversity to systems mimicking natural reefs.

Drawbacks of Hydroids:

- Stinging Corals: Their nematocysts can harm sensitive coral tissue.

- Rapid Reproduction: Outcompete desirable organisms for space and nutrients.

- Visual Nuisance: Dense mats can be unsightly and hard to control.

Tamara’s Pro Tip: Hydroids might be fascinating at first glance, but when they start stinging your favorite corals, the charm fades fast! I recommend removing them as soon as you see them.

Causes of Hydroid Outbreaks

Understanding the root causes of hydroid outbreaks is key to managing and preventing them effectively. These tiny invaders thrive when tank conditions inadvertently favor their growth. Let’s dive deeper into the main culprits:

1. Excess Nutrients

- What Happens: Elevated levels of nitrates and phosphates create a nutrient-rich environment perfect for hydroid proliferation. These nutrients fuel algae and other microscopic organisms, providing an indirect food source for hydroids.

- Sources of Excess Nutrients:

- Overfeeding (direct addition of uneaten food).

- Poor filtration or inefficient nutrient export.

- Detritus buildup in hard-to-reach areas.

- Use of subpar source water, such as untreated tap water.

- The Science: Hydroids rely on nutrient-dense water to support their rapid growth and reproduction. High nutrients accelerate their life cycle and can lead to explosive population growth.

2. Overfeeding

- What Happens: Uneaten food sinks to the bottom of the tank, decomposes, and releases nitrates and phosphates into the water. Hydroids may directly consume organic particles or benefit from the nutrient boost in the water column.

- Common Mistakes:

- Feeding too much at once.

- Not accounting for slow eaters, leaving food to rot.

- Overuse of powdered coral foods or plankton.

- Impact: Hydroids settle near nutrient-rich areas, such as feeding zones, and begin to thrive, forming colonies on rocks or substrates close to uneaten food.

Tamara's Pro Tip: Feed smaller amounts and monitor your fish and coral to ensure all food is consumed within a few minutes. Use a turkey baster to remove uneaten food if necessary.

3. Low Flow Areas

- What Happens: Hydroids prefer stagnant zones where water flow is weak. These areas allow particles to settle, creating ideal conditions for hydroids to anchor and feed.

- Causes of Low Flow:

- Inefficient placement of powerheads or wavemakers.

- Overcrowded aquascaping, creating dead zones behind rocks.

- Inadequate flow settings on filtration systems.

- The Science: Strong, turbulent flow prevents detritus from settling and disrupts hydroid larvae from settling and establishing colonies. Conversely, stagnant areas provide a haven for growth.

Tamara's Pro Tip: Regularly monitor tank flow and adjust powerhead placement to eliminate dead spots, especially around live rock and corners. As corals grow it will change the flow patterns in your tank.

4. Hitchhikers

- What Happens: Hydroids are masters of stealth and often enter aquariums as tiny hitchhikers on live rock, frag plugs, or even invertebrates. Once introduced, they can spread quickly if conditions allow.

- Common Entry Points:

- Newly added live rock from the ocean.

- Unquarantined coral frags with hidden colonies or larvae.

- Invertebrates like hermit crabs or snails carrying hydroids on their shells.

- The Science: Many hydroid species have resilient life stages, like spores or polyps, that can survive transport and quickly reproduce in favorable conditions.

Tamara's Pro Tip: Always quarantine new additions and inspect live rock and coral frags for signs of hydroids. Coral dips and manual scrubbing can remove visible colonies before introducing them to the tank.

Manual Removal:

Manual removal is often the first line of defense when dealing with hydroids, especially when infestations are localized. While it requires time and patience, it’s an effective way to physically eliminate these pests from your tank. Here’s how to do it right:

Tools You’ll Need

- Toothbrush: Perfect for scrubbing hydroids off hard surfaces like live rock or frag plugs. Use a soft-bristle brush to avoid damaging delicate structures.

- Tweezers: Ideal for plucking individual hydroids or pulling out small colonies growing in hard-to-reach places.

- Scrapers: Glass scrapers or razor blades can help remove hydroids from flat surfaces, such as aquarium walls or smooth rockwork.

- Siphon or Turkey Baster: Use during removal to suck out debris and prevent loose hydroid fragments from spreading in the tank.

Steps for Manual Removal

- Turn Off Flow: Turn off pumps or powerheads to prevent hydroid fragments from dispersing in the water column.

- Target the Infestation: Identify areas with hydroids, focusing on rockwork, frag plugs, or substrate where colonies are anchored.

- Scrub or Pluck:

- Use the toothbrush to gently scrub hydroids off surfaces. Apply enough pressure to dislodge them without damaging the underlying material.

- For small, isolated hydroids, use tweezers to pluck them at the base, ensuring the entire polyp is removed.

- Siphon Debris: Immediately siphon away dislodged hydroids and debris to prevent regrowth elsewhere in the tank.

- Rinse Tools: Rinse tools in fresh water or a bleach solution after use to ensure no hydroid fragments remain.

Cautionary Notes

-

- Avoid Fragmentation: Be meticulous during removal, as leftover fragments or polyps can regenerate into new hydroids. Take care not to crush them into smaller pieces that may settle elsewhere.

- Protect Yourself: Some hydroids can sting or irritate skin. Wear gloves during removal to avoid accidental contact.

- Repeat the Process: Hydroids can be persistent, so regular inspections and follow-up removals may be necessary.

Fish That Eat Hydroids:

1. Butterflyfish

- Likelihood: High

- Examples:

- Copperband Butterflyfish (Chelmon rostratus)

- Klein’s Butterflyfish (Chaetodon kleinii)

- Longnose Butterflyfish (Forcipiger flavissimus)

- Effectiveness: Many butterflyfish have a natural tendency to graze on small invertebrates, including hydroids. They are often used to control pest populations in reef tanks.

- Caution: These species may nip at coral polyps, so they are not always reef-safe.

2. Filefish

- Likelihood: High

- Examples:

- Bristletail Filefish (Acreichthys tomentosus)

- Matted Filefish (Acreichthys sp.)

- Effectiveness: Known for eating a variety of pests, including hydroids, aiptasia, and other small invertebrates.

- Caution: Some filefish may also snack on corals or clams, so they should be monitored closely in reef tanks.

3. Wrasses

- Likelihood: Moderate to High

- Examples:

- Six-Line Wrasse (Pseudocheilinus hexataenia)

- Melanurus Wrasse (Halichoeres melanurus)

- Yellow Coris Wrasse (Halichoeres chrysus)

- Effectiveness: Wrasses are opportunistic feeders that may pick at hydroids, particularly smaller colonial species.

- Caution: These wrasses are generally reef-safe but may prey on small ornamental invertebrates like shrimp.

4. Dottybacks

- Likelihood: Moderate

- Examples:

- Orchid Dottyback (Pseudochromis fridmani)

- Neon Dottyback (Pseudochromis aldabraensis)

- Effectiveness: Dottybacks are known to consume small invertebrates, including hydroids, while foraging.

- Caution: They can be aggressive, particularly in smaller tanks, so compatibility should be considered.

Invertebrates Likely to Eat Hydroids

1. Nudibranchs (Berghia sp. or Similar Species)

- Likelihood: High

Certain nudibranchs are highly specialized feeders and may target hydroids, especially colonial varieties. They use their radula (a tongue-like structure) to scrape and consume hydroids directly from surfaces. - Challenges: Nudibranchs often have very specific diets and may only consume certain hydroid species. They are also sensitive to tank conditions, requiring stable parameters.

2. Emerald Crabs (Mithraculus sculptus)

- Likelihood: Moderate to High

Emerald crabs are known for eating nuisance algae but are opportunistic feeders that will graze on small invertebrates, including hydroids, if they encounter them. - Challenges: While effective in some cases, they are not guaranteed to eat hydroids exclusively and may turn to easier food sources if available.

3. Peppermint Shrimp (Lysmata wurdemanni)

- Likelihood: Moderate to High

Peppermint shrimp are popular for their ability to consume aiptasia anemones, but they may also pick at hydroids as part of their diet. They are most effective against smaller colonial hydroids. - Challenges: Shrimp may ignore hydroids if other food is more accessible, and not all peppermint shrimp species have the same feeding habits (ensure you get Lysmata wurdemanni and not a look-alike species).

4. Urchins (Tuxedo Urchin – Mespilia globulus)

- Likelihood: Moderate

Tuxedo urchins are constant grazers, eating algae and small organisms, including hydroids, that grow on rock surfaces. They’re particularly effective in keeping surfaces clean, reducing hydroid settlement. - Challenges: Urchins are generalists and may not focus on hydroids specifically. They can also knock over loose rockwork or corals while grazing.

5. Hermit Crabs (Various Species)

- Likelihood: Moderate

Hermit crabs, particularly larger species like the Scarlet Hermit Crab (Paguristes cadenati), may pick at hydroids while grazing on algae and detritus. Their constant foraging can incidentally help control hydroid populations. - Challenges: Hermits are opportunistic and may not target hydroids consistently. Additionally, they might compete with other clean-up crew members for food.

Chemical Treatments:

When manual removal and natural predation aren’t enough to manage hydroids, chemical treatments can offer a more targeted solution. However, these methods must be used carefully to avoid unintended harm to corals, invertebrates, and other tank inhabitants. Below, we’ll dive deeper into popular chemical approaches and how to apply them effectively.

1. Kalk Paste

- What It Is: Kalk paste is a concentrated slurry made by mixing calcium hydroxide (kalkwasser) with water to form a thick paste.

- How It Works: The paste is applied directly to the hydroids, effectively "burning" them by altering the pH and calcium concentration at the site of application. This kills the hydroids while leaving the surrounding area mostly unaffected.

- Application Steps:

- Turn off powerheads and pumps to prevent the paste from dispersing.

- Use a syringe or small applicator to apply the paste directly to the hydroids.

- Allow the paste to sit for 5–10 minutes before turning water flow back on.

- Siphon any excess paste to avoid impacting water chemistry.

- Caution:

- Overuse of kalk paste can spike pH or calcium levels, potentially harming tank inhabitants.

- Use sparingly and monitor water parameters after application.

2. Hydroid-Specific Treatments

- What They Are: These are reef-safe chemical solutions specifically designed for pest control, including hydroids. Brands like Aiptasia-X and F-Aiptasia may also work against certain hydroid species.

- How It Works: These treatments typically contain compounds that disrupt the cellular function of hydroids, killing them on contact.

- Application Steps:

- Follow the manufacturer’s instructions carefully to ensure safe use.

- Use a syringe to apply the treatment directly to the hydroids, covering the colony thoroughly.

- Repeat treatments as necessary for stubborn infestations.

- Caution:

- Avoid over-application, as even reef-safe products can stress corals and other invertebrates if used in excess.

- Test the treatment in a small, isolated area before widespread use to observe any unintended effects.

3. Risks and Precautions

- Chemical Risks:

- Tank-Wide Effects: Even localized treatments can impact water chemistry, especially in smaller tanks with less stability.

- Collateral Damage: Some treatments may harm beneficial organisms or stress sensitive corals.

- Testing First:

- Always test chemical treatments in a controlled environment, such as a quarantine tank or isolated area, before applying them to the display tank.

- Monitor water parameters (e.g., pH, alkalinity, calcium) after treatment to ensure stability.

- Safety for Tank Inhabitants:

- Ensure treatments are labeled as reef-safe and compatible with the organisms in your tank.

- Avoid applying treatments near corals, anemones, or other sensitive invertebrates.

When to Use Chemical Treatments

-

- Persistent Infestations: If hydroids continue to return despite manual removal and natural predation, chemical treatments can be a last resort.

- Localized Outbreaks: Best suited for targeting specific areas without affecting the entire tank.

Environmental Adjustments:

Adjusting your tank’s environment can significantly hinder hydroid growth and spread. By targeting the conditions they thrive in, you can make your tank less hospitable to these unwanted pests while maintaining a healthy ecosystem for your desired inhabitants.

Nutrient Reduction

- How It Helps: Hydroids thrive in nutrient-rich environments, feeding on organic particles and microscopic plankton. Reducing excess nutrients limits their food supply and slows their growth.

- Steps to Reduce Nutrients:

- Water Changes: Perform regular water changes to dilute nitrates and phosphates. Aim for a schedule that aligns with your tank’s bioload (e.g., 10–20% weekly or bi-weekly).

- Improved Filtration: Use efficient filtration systems, such as protein skimmers, to remove dissolved organics before they break down into nutrients.

- Use Phosphate Removers: Add GFO (granular ferric oxide) or similar media to lower phosphate levels.

- Feed Less: Avoid overfeeding and remove uneaten food promptly to prevent nutrient buildup.

Increased Water Flow

- How It Helps: Hydroids prefer low-flow areas where detritus settles and larvae can attach easily. Increasing water flow disrupts these conditions, making it harder for hydroids to establish colonies.

- Steps to Increase Flow:

- Powerheads and Wavemakers: Add or reposition powerheads to eliminate dead spots in your tank, especially behind rock structures and in corners.

- Flow Patterns: Use wave modes or alternating flow patterns to create turbulence, mimicking natural reef conditions.

- Maintain Equipment: Regularly clean and service pumps to ensure optimal flow performance.

Preventing Hydroid Outbreaks

Prevention is the best cure. Here’s how to stop hydroids before they take over:

- Maintain Clean Water:

- Regular water changes to remove nitrates and phosphates.

- Use a high-quality protein skimmer to export organic waste.

- Inspect New Additions:

- Quarantine and dip live rock, coral frags, and invertebrates to eliminate hitchhikers.

- Don’t Overfeed:

- Feed sparingly and remove uneaten food to reduce nutrient buildup.

Myths About Hydroids

Hydroids are one of those pests that come with plenty of misconceptions. Let’s separate fact from fiction and get to the truth behind these myths:

1. "Hydroids only appear in dirty tanks."

Reality:

Even the cleanest, most well-maintained tanks can host hydroids. These pests often sneak in as hitchhikers on live rock, coral frags, or even invertebrates. While nutrient-rich water may encourage their growth, they can establish themselves in low-nutrient systems if other conditions (like low flow or excess detritus in certain areas) are favorable.

- Why It Happens:

- Hydroids are opportunistic and can adapt to various environments.

- Tiny larvae or polyps can remain hidden during inspections, making it easy for them to gain entry.

- What to Do:

- Quarantine all new additions.

- Maintain strong flow and regularly clean areas where detritus accumulates.

2. "Hydroids will go away on their own."

Reality:

Hydroids rarely, if ever, disappear without some form of intervention. In fact, they tend to spread and worsen over time if left unchecked. Many hydroids reproduce both sexually and asexually, which allows them to establish colonies quickly.

- Why They Persist:

- Their ability to regenerate from fragments means partial removal isn’t enough.

- Free-swimming medusa (in some species) can establish new colonies across the tank.

- What to Do:

- Address infestations promptly with a combination of manual removal, nutrient control, and, if necessary, targeted treatments.

- Remove hydroid fragments and medusa to prevent further spread.

Tamara’s Pro Tip: Ignoring hydroids is like ignoring a tiny fire—it’ll just get bigger and more destructive.

3. "Chemicals are the only way to remove hydroids."

Reality:

While chemical treatments like kalk paste or hydroid-specific solutions can be effective, they’re not your only option. In fact, combining multiple methods often yields better results. Manual removal, introducing natural predators, and making environmental adjustments can significantly reduce hydroid populations without relying solely on chemicals.

- Alternatives to Chemicals:

- Manual Removal: Use tools like tweezers or a toothbrush to scrape off hydroids from surfaces.

- Natural Predators: Certain fish (e.g., butterflyfish, filefish) and invertebrates (e.g., peppermint shrimp, nudibranchs) will consume hydroids.

- Environmental Adjustments: Increase water flow, improve filtration, and reduce excess nutrients to create unfavorable conditions for hydroids.

FAQs

Q: Are hydroids dangerous to humans?

A: Most hydroids are harmless to humans, but some species have stinging cells that can cause mild skin irritation or a burning sensation. Always wear gloves when handling hydroids or working in a tank with an infestation to avoid contact.

Q: Can hydroids kill corals?

A: Yes, hydroids can sting nearby corals with their nematocysts, causing tissue damage and stress. Over time, this can lead to coral death, particularly in species that are already weakened or struggling to compete for space and nutrients.

Q: What’s the fastest way to remove hydroids?

A: For small outbreaks, manual removal using tools like tweezers, toothbrushes, or scrapers is effective. Pair this with targeted chemical treatments, such as kalk paste or reef-safe hydroid removers, for stubborn infestations.

Q: Can hydroids come back after removal?

A: Yes, hydroids can regenerate from fragments left behind during removal. Additionally, some species produce free-swimming medusa that can establish new colonies elsewhere in the tank. To prevent regrowth, remove all fragments and consider nutrient and flow adjustments.

Q: How do hydroids get into a tank?

A: Hydroids often hitchhike on live rock, frag plugs, or new tank additions like corals and invertebrates. Their larvae are microscopic and can evade visual inspection, making quarantine and dipping protocols essential for prevention.

Q: Will reducing nutrients eliminate hydroids?

A: While nutrient reduction can slow hydroid growth and prevent outbreaks, it is rarely enough to eliminate an established infestation. Nutrient control should be paired with manual removal and other intervention methods for the best results.

Q: Are all hydroids equally harmful?

A: No, some hydroids are more aggressive and invasive than others. Colonial hydroids, for example, spread rapidly and can smother corals, while solitary hydroids are less invasive but still pose a threat due to their stinging cells.

Conclusion

Hydroids may be tiny, but their impact on a reef tank can be huge. Whether you see them as a minor nuisance or a serious threat, understanding their biology and behavior is key to managing them effectively. With the right combination of manual removal, natural predators, and preventative care, you can keep hydroids in check and ensure your tank remains a thriving, healthy ecosystem.

Happy Reefing!

.png)